JWhat features of the orchid made you immediately pay attention to its uniqueness?

It was these “angelic” wings on a labellum. In orchids, the central petal, called the lip (labellum), is usually significantly different from the rest of the petals. It serves as a decoy that attracts insects to pollinate. It acts as a decoy to attract the right insects and allow pollination. This is what we focus on when looking for differences between species, as each attracts specific pollinators. Thanks to this specialisation, pollination by pollen of individuals of the same species most often occurs. I have never seen a labellum with such “wings” before. This orchid is truly unique, one of a kind.

Is this one one of a kind even though the genus Telipogon has many species?

Exactly. In the genus Telipogon there are, as far as I remember correctly, more than two hundred and fifty species, but this one immediately stood out. Few of them have a concave lip, like T. angelicus, and these distinctive “wings” immediately suggested that I had something completely new in front of me.

Purpose of the expedition and the process of discovery

Did you embark on this journey with the intention of discovering new species? What was its main goal?

I sort of ‘tagged along’ on a trip organised by two friends – one from the United States and the other from Belgium. They are engaged in the study of large flowered orchids of the genera Cyrtochilum and Odontoglossum, so they already had all the logistics organised: the driver, the route, the back office. I took the opportunity and joined them.

On the other hand, I was looking for rare and new species – this is the main goal of my field trips: discovering what has not yet been described. In Colombia, I also conduct permanent, long-term studies on diversity and population dynamics in designated areas, but in Peru I focused exclusively on intensive screening of the site for new orchids.

What does the process of confirming that a plant is a new species look like?

In most cases, it is really a journey through torment – but for me it is the most interesting, almost detective part of the work. First, we need to make sure that the plant in question has certainly not already been described before. This requires tracing all the names that may have been given to it. At the beginning of the exploration of South America, every orchid brought to Europe was considered new, so many researchers described the same species independently of each other – which is why today some of them have several synonymous names.

The difficulty is also very laconic historical descriptions – sometimes just a few lines that say little about the real appearance of the plant. And we today have to distinguish species on the basis of increasingly subtle details.

When doubts arise, the real investigation begins: you have to reach the holotype – usually a dried specimen stored in one of the herbarium sheets – and see it in person. Since in the old days there were no photographs and the illustrations were of very different quality, each such verification is a little travel in time and putting together puzzles with very incomplete information. Only then can we say with full confidence whether we have discovered something really new.

The function of wings and research.

The labellum in Telipogon has certain structures. What element of the structure of the flower is of the greatest diagnostic importance?

There is usually a callus, that is, an outgrowth on the labellum in Telipogon. It is suspected that a phenomenon of pseudocopulation occurs in this group of orchids. This involves the flower or part of it resembling a female insect, and the male arrives and attempts to mate with it, taking pollen with him in the process. This callus structure must be very specific for the insect to actually be fooled. This is the element that we are paying attention to. Old descriptions often focused on the colour, but colours are rarely diagnostic features because they can depend on the environment.

What is the significance of these wings? Do they have any function?

The most unusual are precisely these “wings”. Do they have a specific function? For now, we don't know. They most likely have to do with attracting pollinators – so that the insect is encouraged to arrive and interact with the flower.

We do not yet have chemical analyses, but it is possible that these structures may produce pheromone-like compounds that further enhance the effect of pseudocopulation. This is one of the hypotheses that we would like to verify in future studies.

Will you do further research on this orchid to find it out?

Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult to obtain permits for chemical research in South America. Many institutions fear that researchers in Europe or the United States may discover something potentially valuable – such as a substance of medical importance – and “export” the profit outside the country. For this reason, for the time being we must limit ourselves to taxonomic and morphological studies. The fact that orchid grows high in the mountains and is virtually impossible to cultivate under controlled conditions constitutes a additional challenge. It needs a specific mycorrhizal partner to germinate, and current research indicates that throughout its life it remains strictly dependent on a specific species of fungus that supports its functioning in the harsh conditions of the tropics.

Telipogon species are generally very difficult to maintain outside their natural habitat – they simply die in cultivation.

Research challenges and conservation

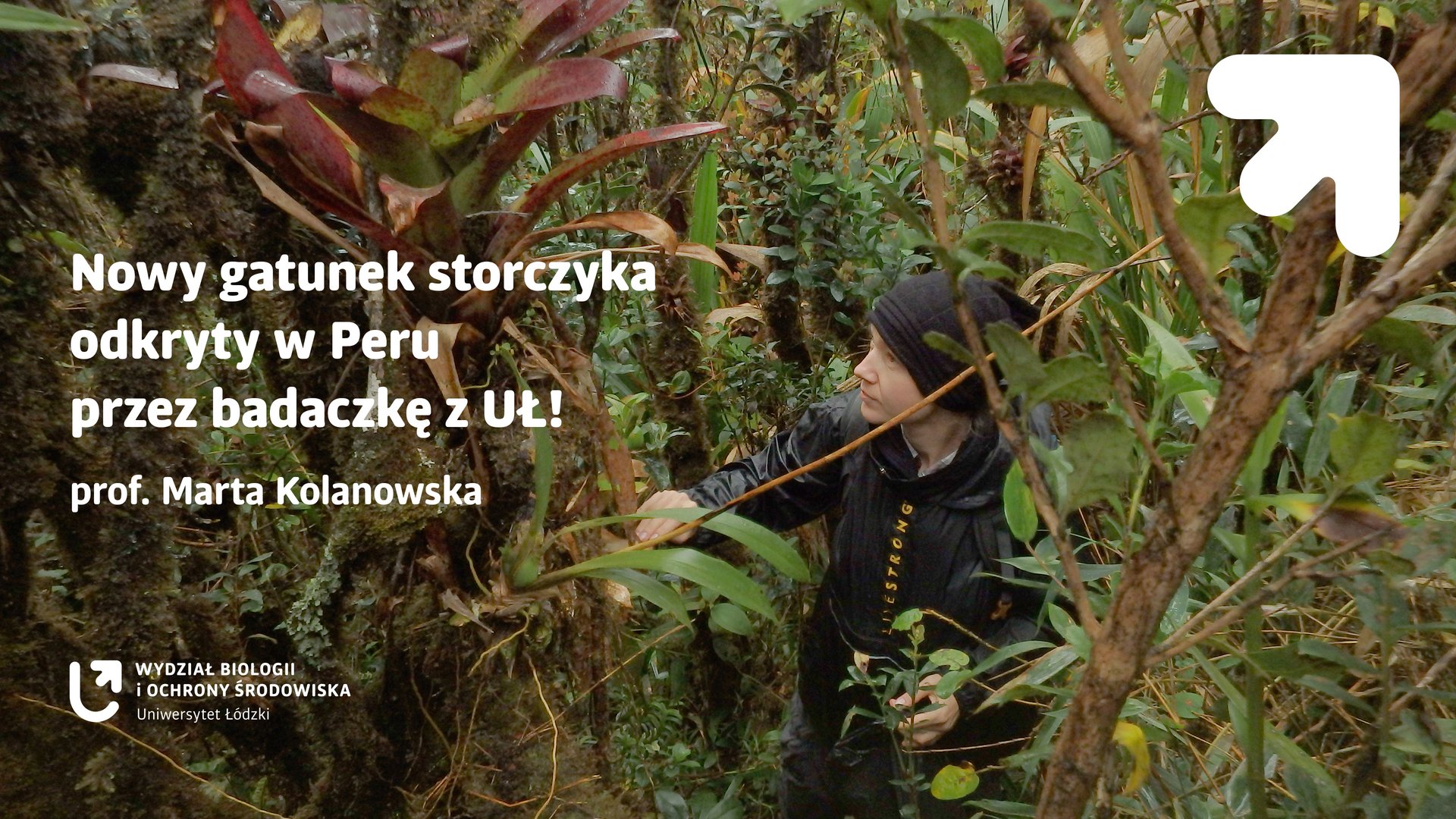

What are the biggest challenges of conducting research in the Andes?

First and foremost, the Andes are wet and cold, and then there is the altitude — and that is a matter of individual adaptation of the body. I'm lucky enough to have trained in judo, I run a lot, so I usually tolerate such conditions well... but it's a lottery.

I remember one time in La Paz – above 4,000 meters above sea level – I could barely stay on my feet after getting off a plane. Height can make itself felt instantly, even if one is theoretically prepared for it.

Is the area you visited protected or restricted?

No, I usually work outside of protected areas. Many national parks and reserves have already been well studied, and I am most attracted to uncharted areas, ones that science rarely looks into.

How do you get there? In the Andes, the lower parts of the mountains are mostly occupied for pastures or crops. Only where it is difficult for people to reach and there are no roads does true wilderness begin. So, first we pass through the utility zone, and later we climb higher.

Unfortunately, climate change is causing agriculture to move higher and higher, and with it the clearing of forests for new pastures. This is a real threat to the habitats of many rare species that have found their refuge in these hard-to-reach parts of the mountains.

Does the discovery of a species in a hard-to-reach place mean that there are more potentially similar species out there?

Yes, it does – it is very possible that since we discover a new species in a hard-to-reach area, there may be many more, undescribed species. The problem is that forests are being cut down faster than we can document their biodiversity. Many species die before anyone can describe them. One scientific model estimates that between 15% and 59% of extinct species are those “undiscovered” ones... Certainly there is much more to discover in these mountainous, poorly studied areas – especially in countries like Peru, which are still a relatively poorly explored part of the Andes.

What factors can most threaten the survival of this orchid?

In the mountains, plants can ‘escape’ higher and higher from climate change, but a mountain has its peak – at some point, there will simply be nowhere left to move. In addition, we do not know if the fungus with which this orchid must enter into symbiosis will also follow the change in environmental conditions.

The population I observed grew on literally two or three trees. A single lightning strike, landslide or tree felling can be enough to destroy it. Changes in the structure of the forest also affect pollinators – if the corresponding insect disappears, the orchids will not have a chance to reproduce.

Some orchids are capable of self-pollination, but species in the genus Telipogon most likely do not – they are dependent on the presence of a pollinator. If they do not reproduce, the population will simply disappear after a while.

Are protective measures being taken for this species?

No, they aren’t – just describing a new species does not automatically mean setting up a reserve. Even if I have already described more than 400 species, protecting their habitats is a completely different matter. In many countries where I work, existing conservation areas are often not effectively managed and do not sufficiently protect rare plants.

When I publish descriptions of new species, and especially those that may be attractive to collectors, I deliberately omit very detailed location data. This is a conservation strategy – to make it harder for people to find these plants who could harvest and trade them.

Hopefully this will help keep them safe from collectors. There have already been cases that after the description of a new species, its entire natural populations were brutally collected and consequently the species almost became extinct (e.g. Paphiopedilum vietnamense).

Emotions, motivation and further plans

What do you feel when you discover a new species?

Excitement is greatest at the moment of discovery. It's a moment when your heart really beats faster – because you suddenly realise that you are holding something in front of you that no one has ever seen or described before.

However, later comes the stage of formalities: review of literature, verification, descriptions, preparation of illustrations, selection of the appropriate journal... All this necessary paperwork can cool down the emotions. Sometimes enthusiasm gets lost under an avalanche of forms and reviews, as if someone had buried it under paperwork.

However, still, knowing that you're adding a new genre to science remains hugely satisfying.

What is the point of discovering and describing a new species?

For me, describing a new species is only the beginning – it is a testament that a given organism existed and was noticed by science, but it does not guarantee that its habitat is protected.

Orchids often act as indicators of the state of the environment. If there are many orchids growing in a given place and the populations are healthy – this is a sign that such an ecosystem is functioning properly: there are suitable pollinators, symbiotic fungi, habitat conditions – all this indicates that the forest is in good condition.

Therefore, the discovery of a new species can be much more important than just another name – it is an alarm signal or confirmation of the conservation values for a given area. If many species of orchids coexist in one place – this place deserves special attention and protection.

Why exactly was this orchid called “angelic”?

I had been hunting for so long for a new orchid that I could call ‘angelic’. I previously described Telipogon diabolicus – meaning “devilish” – so I felt that the other side of the coin was missing.

When I saw this specimen with delicate “wings” on the labellum, I immediately thought that that was it. An ideal candidate for “angelic”. And so Telipogon angelicus was born.

What are your further research plans?

I would like to study even more intensively the flora of the orchids of Colombia. This is my absolute number one – the most orchid-rich country in the world. It has a huge variety of species, plenty of areas still unexplored and probably the most undiscovered orchids yet.

Colombia is like a treasure trove where every expedition can bring something new – and that's what drives me the most.

We know that you only deal with orchids. How many tropical orchid specialists are there in Poland?

There are probably fewer than ten of us who study tropical orchids, and we are all, let us say, from the ‘Gdańsk school’. In Europe, temperate countries have relatively few native orchids – there, indeed, is already “little to describe”. There are about 50 native species in Poland. Meanwhile, in tropical countries like Colombia, orchids represent one of the most diverse groups of plants – more than 4,000 species have already been documented in Colombia, and many are still waiting to be described.

It still remains an unexplored field for discovery. Research into tropical orchids is a niche field that requires passion and determination, but every new plant discovered by science rewards this effort.

Edit and graphics: Mateusz Kowalski, Kamila Knol-Michałowska (Promotion Centre, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz)

Source: Prof. dr hab. Marta Kolanowska (Department of Geobotany and Plant Ecology, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz)

Photos: Stig Dalström